Until the final obliteration of Jewish communities in the occupied lands and the satellite countries, regular postal communications during the Holocaust were usually maintained. Connections with countries adjacent to neutral lands, such as Turkey, or satellites such as Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary, were smoother than those with Poland, which usually took place via Switzerland. Communication with eastern Poland and the Baltic countries was totally cut off in late June 1941 due to the German invasion and occupation of the Soviet territories.

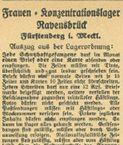

Jews in the occupied areas had to write in German only. The number of words, the contents of the letters, and sometimes even the style of the writing were restricted. All letters were checked by the censor.

In some ghettos, mail distribution was run by the Judenrat (Jewish Council). The postal department was essential to the Judenrat because it was the only official channel of communication between councils and with the outside world. It also provided dozens of staff with an income and the taxes that were applied to postal items and payment for stamps were sources of revenue for the Judenrat coffers. Outgoing mail was always stamped “Judenrat” and carried the stamp of the German censor as well.

The postal services mirrored the living conditions in the occupied areas. In Poland, for example, apart from Łódź, it was easier to send and receive mail in towns under German rule (i.e., annexed to the Reich), where ghettos were not established until late 1942, than in cities such as Warsaw and Kraków, which were administered by the Generalgouvernement. In the latter locations, postal services were often disrupted and many letters never reached their destinations. Once the Aktionnen took place, the services were discontinued.

In large ghettos, ghetto postcards and letters and even special stamps were issued. The stamps of the Łódź ghetto, which carried a portrait of the Chairman of the Judenrat, Mordecai Chaim Rumkowski, are especially well known.